LGBT+ History Month: the Baron Adolph de Meyer

In celebration of LGBT+ History Month I take this opportunity to introduce to you a nowadays somewhat forgotten figure in the history of photography, the fashion and portrait photographer Baron Adolph de Meyer. Born in 1868 in Paris but growing up mostly in Germany, de Meyer was of a German-Jewish and Scottish aristocratic background, who in 1899 entered a marriage of convenience with the beautiful socialite and artist’s model, Olga Caracciolo. They were the Posh and Becks of their day. However, he was homosexual, and Olga either bisexual or lesbian, as well as being a goddaughter of King Edward VII. And possibly even illegitimate daughter, although that’s never been proven! They lived surrounded by London’s high society. Amidst the society gatherings, grand parties, and artistic circles, they enjoyed a certain but very limited amount of freedom within the LGBTQ+ umbrella (as it would be called today). However, the Oscar Wilde scandal of 1895 and the later onset of World War I prompted many to escape from Europe if they could. As a result, the de Meyers moved to New York around 1913 where Adolph became the first staff photographer for Vogue, and also appeared in the sister publication Vanity Fair.

Up until the early twentieth century, images in fashion magazines were either produced from drawings or rather formulaic and uninspiring studio photographs. These shots normally comprised of painted backdrops, generic poses, and natural daylight or studio lighting which provided an evenly lit space throughout the scene. As an emerging pictorialist photographer who believed in image making as a form of art, de Meyer’s expert darkroom printing techniques and understanding of light, texture and tone, allowed him to move away from this more traditional approach. Through this shift, it was he who invented the genre of fashion photography which paved the way forward for the more eye-catching fashion imagery that we know today. He regularly experimented with creative, artificial backlighting, and he often used diffused lighting by stretching gauze over the camera lens. Differential focusing was also a regular tool, where the centre of an image could be sharp and in focus but leading to a graduated softening around the edges.

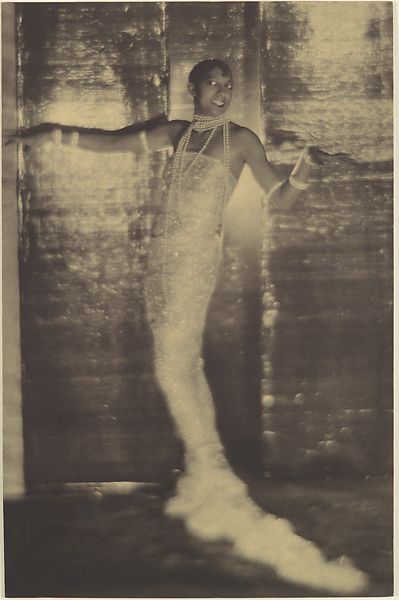

Fig. 1 Josephine Baker, c1925

Direct carbon print, 45.2cm x 29.5cm, The Met Museum, New York

One image which clearly demonstrates some of these techniques is that of Josephine Baker, taken c1925 (fig. 1); who was an entertainer, civil rights activist, and a French Resistance operative during World War II. In this photograph, Baker is framed within a highly reflective backdrop which complements the sparkling dress and pearls. The dreamy and atmospheric effect is also accentuated by much of the bottom half of the image being in soft focus. From her facial expression, the image seems to capture a slightly unusual moment in her comedic stage personality, indicating with little certainty of what may have happened just before the shot was taken. In an essay on de Meyer, Anne Ehrenkranz suggests that Baker was one of the numerous women photographed by the artist, who were starting to experience the freedom and sexuality of a new and uneasy age; and in portraying them he adopted a similar approach to the artist Gustav Klimt of emphasizing the psychological condition, and often with a distinctive linear style (1994, p. 17). There is a definite similarity between this image and the many full-length paintings executed by Klimt during the early twentieth century. Just look at the portraits of Gertrud Loew (fig. 2) or Emilie Flöge (fig. 3) as prime examples. Female sitters, often with signs of inner turmoil or struggle apparent in their faces, and framed within elegant settings or reflective backdrops. With a familiarity Klimt’s work, de Meyer would very likely have been thinking of paintings such as these when capturing the long, slimline dress of Josephine Baker.

Fig. 2 Gustav Klimt, Portrait of Gertrud Loew, 1902

Oil on canvas, private collection

Fig. 3 Gustav Klimt, Portrait of Emilie Flöge, 1902

Oil on canvas, Vienna Museum

Some of de Meyer’s best work featured a distinctive luminous effect, which was something very new to fashion and portrait photography at the time. A master of his trade, he would fix silk over his filters, drape his female sitters in satin or transparent materials, spill buckets of water on marble flooring, or even spray flowers with artificial dew. In the photograph Jeanne Eagels of 1921, used in Vogue magazine (main image), the French actress is seen leaning across a table staring intently towards a vase. Backlighting provides highlights to the hair and the outline of her face, whilst additional lighting creates a strong reflection on the vase and transforms the plant into a beacon of luminosity. From a contemporary viewpoint, we could say there is a gay sensitivity at work here. Perhaps aided by his sexuality, de Meyer understood the delicacy and femininity required to produce a photograph such as this. The image is converted into a fairy tale scene with both Jeanne Eagels and the viewer, transfixed on the plant. An article in The Craftsman magazine from the period explains that ‘he deliberately focuses his camera not upon the sparkle of an eye but upon the light that illuminates the eye’ (1914, p. 51). Although not referring specifically to this image, it does give a clear idea of the thinking behind de Meyer’s creativity, by observing and reacting to the effect of light on different surfaces.

Having returned to Paris in the 1920s to work for Harper’s Bazaar where he enjoyed greater control over the images he produced, by the 1930s a harder edged style of fashion imagery had emerged. De Meyer was eventually replaced at the magazine as his photography was considered outdated. Olga passed away in 1931 and Adolph returned to the United States just before the outbreak of World War II, again to escape the troubles in Europe. Usually reported as either his partner or his adopted son (he was probably both), de Meyer lived with the much younger German, Ernest Frohlich, until his death in 1946. Cecil Beaton once wrote ‘Of the poor, pathetic phantoms of the past, a faint memory of the day before yesterday, the Baron de Meyer is forgotten today by all but a few who still appreciate the contributions he made to this time in Vogue’s pages’ (2014, p. 108). Adolph de Meyer. Truly a figure who should indeed be remembered, in both LGBT+ history month and in the history of photography.

Beaton, C. (2014). The Glass of Fashion: A Personal History of Fifty Years of Changing Tastes and the People Who Have Inspired Them. New edn. New York: Rizzoli Ex Libris.

Ehrenkranz, A. (1994). Essay. In: Ehrenkranz, A. Hartshorn, W. and Szarkowski, J. A Singular Elegance: The Photographs of Baron Adolph de Meyer. San Francisco: Chronicle Books, pp. 13-49.

The Craftsman (1914). The Artist’s Wonder-Stone: How Baron de Meyer Sees Modern Spain. The Craftsman, October 1914, pp. 46-52.